Muscicapoidea

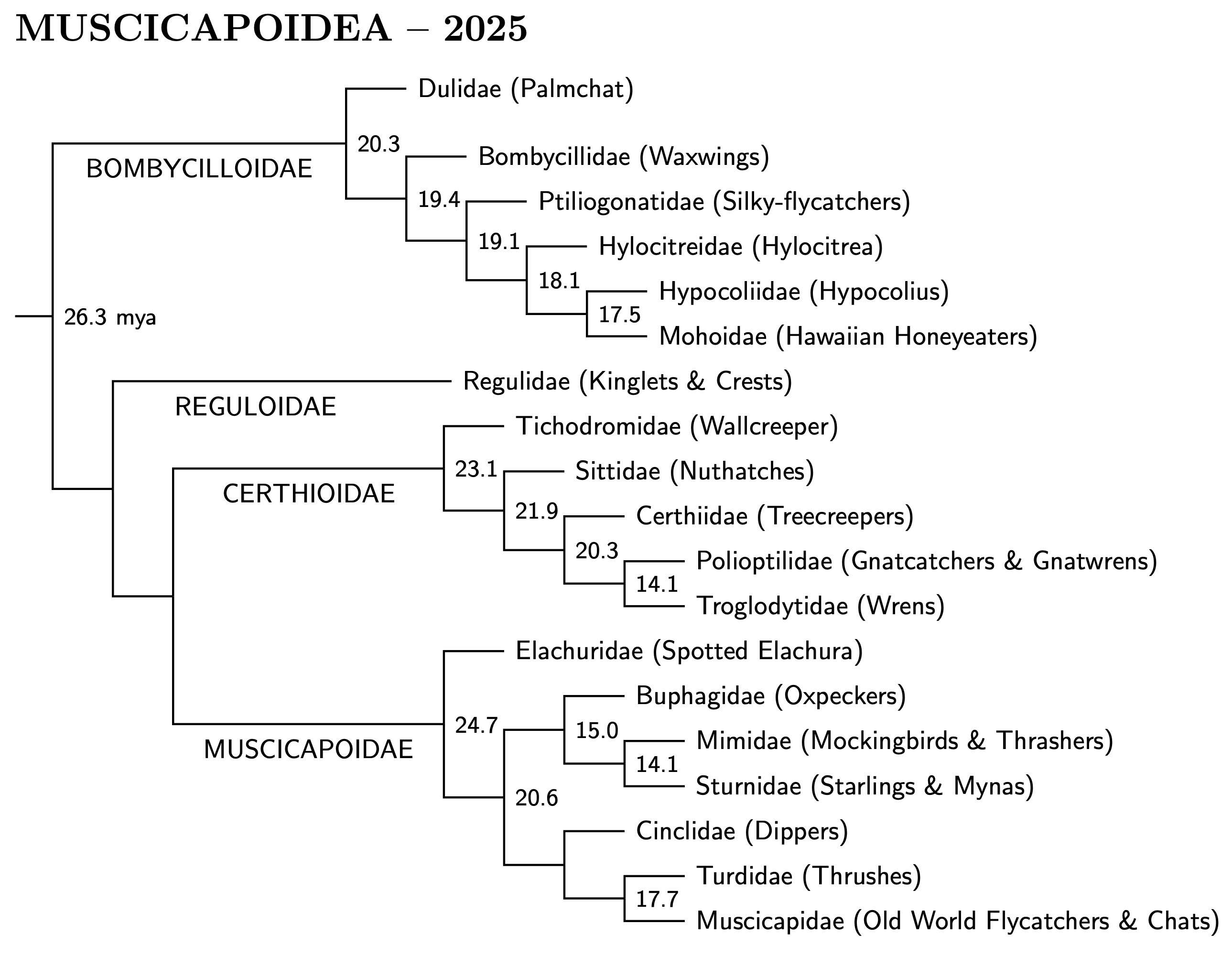

I've changed the ranks of the clades most closely related to the Muscicapoidea. The clades in the Muscicapoidea group that were previously ranked as superfamilies have all been demoted to epifamilies. This changes the spelling so that the names end in -oidae instead of -oidea. It's a subtle change in name.

That gives us four epifamilies: Bombycilloidae, Reguloidae, Certhioidae, and Muscicapoidae in the old Muscicapoidea group. The clade containing them is now given the name Muscicapoidea, which I'll sometimes call Big Muscicapoidea to make clear I mean the expanded Muscicapoidea. The Big Muscicapoidea is on about the same level as Passeroidea and Sylvioidea. In fact, Big Muscicapoidea is sister to Passeroidea, and the two together are sister to Sylvioidea.

There is one change to the membership of the epifamilies. The Spotted Elachura has been removed from Bombycilloidae. According to Oliveros et al. (2019) and Stiller et al. (2024) it is on the basal branch Muscicapoidae. Note that Kuhl et al. (2021) is silent on this, having not sampled Elachura.

|

| Big Muscicapoidea tree |

|---|

The phylogeny above derives from Oliveros et al. (2019), Kuhl et al. (2021), and Stiller et al. (2024), with a little help from Zhao et al. (2025). A few decisions had to be made since these papers are not in complete agreement.

Oliveros et al. (2019) is the only paper to sample all of the families in Australaves (64% of all birds). Of the Muscicapoidea, Stiller et al. (2024) only includes two of the Bombycilloidae. Kuhl et al. (2019) include only 3 of the 6 Bombycilloidae, and also omit Elachura. The only actual conflicts between the big three are (1) the position of Regulidae (kinglets) where there is complete disagreement, of (2) Cinclidae (dippers), where Oliveros et al. disgree with Kuhl et al. and Stiller et al., and of (3) the arrangement within Bombycilloidae, where the three families sampled by Kuhl et al. are grouped differently than in Oliveros et al.

I've positioned Regulidae as in Stiller et al. (2024) and Zhao et al. (2025). In contrast, Oliveros et al. (2019) place Regulidae sister to Certhioidae, and Kuhl et al. (2021) have it sister to Bombycilloidae. Additionally, Oliveros et al. have the dippers sister to five families: oxpeckers through flycatchers and chats. The Bombycilloidae tree also differs slightly from Kuhl et al.. Specifically, the three Bombycilloidae included by Kuhl et al. are arranged differently there. Oliveros et al. Zhao et al. and Oliveros et al. almost agree on Bombycilloidae. The only difference is that Hylocitrea and Hypocolius are on successive branches in Oliveros and are sister taxa in Zhao et al.

The estimated node ages are in millions of years ago (mya). The use of consensus ages wasn't as practical here due to missing data and conflicting nodes. Oliveros et al. (2019) have the most complete treatment, and I've used their ages, but only for the nodes where they apply. The nodes without ages are not present in Oliveros et al.

Why is Muscicapoidea not called Turdoidea?

The name doesn't seem to follow ICZN rules. The name Turdidae has priority over Muscicapidae (1815 vs. 1822), and that should also be true for any family-group name, including Turdoidea over Muscicapoidea. The answer may be tradition.

Everyone uses Muscicapoidea, which lacks priority. In fact, a search revealed only a few uses of Turdoidea, and those only for groups not containing Muscicapidae. According to Bock (1994) the name Muscicapoidea ``has been consistently used over the past several decades in discussions of passerine classification.'' Keep in mind that his book was published over 30 years ago, so he asserts its been in use for over six decades. Unfortunately, Bock did not give any references. The earliest I could find on Google Scholar were Cracraft (1981) (who also uses Muscicapi for the suborder Passeri) and Sibley and Ahlquist (1981).

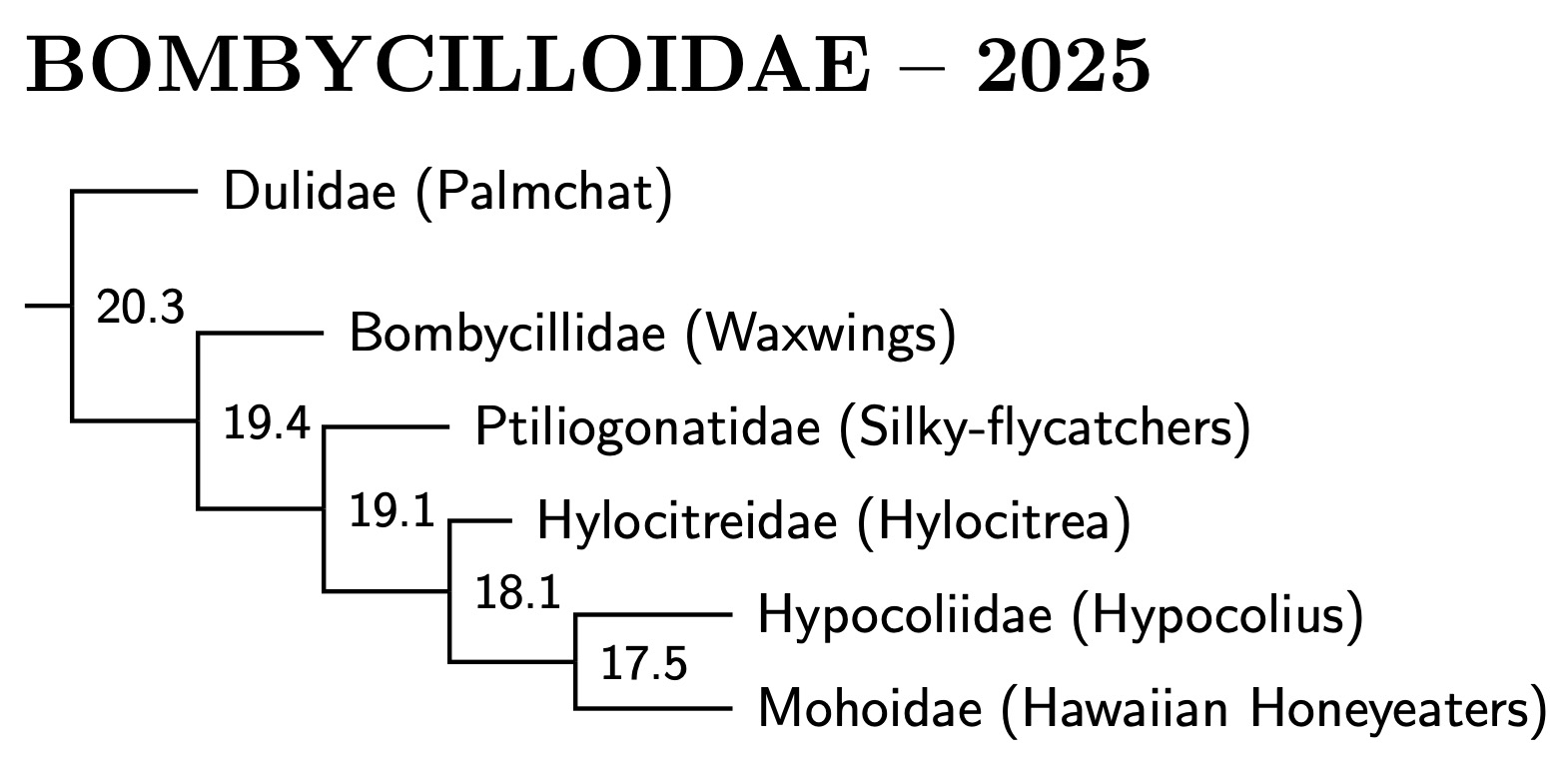

Bombycilloidae

The Bombycilloidae have only slowly been discovered. The palmchat, waxwings and silky-flycatchers have been considered relatives since the 19th century. Some authors started including the Gray Hypocolius in the group in the 1950's, but it had also been placed in Sylvioidea, even by Sibley and Ahlquist (1990). The Mohoidae were considered honeyeaters (Meliphagidae), and the Hylocitrea was considered a whistler (Yellow-flanked Whistler).

I had previously relied on Spellman et al.'s (2008) comprehensive study of the waxwings and allies, on Fleischer et al. (2008) for the mohos, and on Alström et al. (2014). As Spellman et al. note, the surprising inclusion of Hylocitrea “further demonstrates the need to reconsider the systematics of many Wallacean taxa using molecular techniques.” Needless to say, it was a surprise when Alström et al. (2014) suggested including Elachura in the group.

Oliveros et al. (2019) and Stiller et al. (2024) both put Elachura in the Muscicapoidae instead. Although Stiller et al. did not consider enough taxa from the Bombycilloidae to say much other than about the age of the group, Oliveros et al. included all six families. The current arrangement of the families follows Oliveros et al.

The recent publication by Zhao et al. (2025) included all 15 Bombycilloidae

species, even the five extinct Mohoidae. The family-level phylogeny is almost

the same as in Oliveros, except Zhao et al. found Hypocolius and

Hylocitrea to be sisters rather than adjacent branches as in Oliveros

et al.

The recent publication by Zhao et al. (2025) included all 15 Bombycilloidae

species, even the five extinct Mohoidae. The family-level phylogeny is almost

the same as in Oliveros, except Zhao et al. found Hypocolius and

Hylocitrea to be sisters rather than adjacent branches as in Oliveros

et al.

It may seem crazy to have so many families for a small number of species, but the divisions between them are deep (17.5 to 20.5 mya) and each family is obviously different from the others.

Dulidae: Palmchat P.L. Sclater, 1862

1 genus, 1 species HBW-10

- Palmchat, Dulus dominicus

Bombycillidae: Waxwings Swainson, 1831

1 genus, 3 species HBW-10

As with most other families in Bombycilloidae, the placement of the waxwings is based on Oliveros et al. (2019) and Zhao et al. (2025). Their arrangement follows Zhao et al. (2025).

- Bohemian Waxwing, Bombycilla garrulus

- Japanese Waxwing, Bombycilla japonica

- Cedar Waxwing, Bombycilla cedrorum

Ptiliogonatidae: Silky-flycatchers Baird, 1858

3 genera, 4 species HBW-10

The original spelling Ptiliogonys has been restored. See Gregory and Dickinson (2012).

- Black-and-yellow Silky-flycatcher / Black-and-yellow Phainoptila, Phainoptila melanoxantha

- Phainopepla, Phainopepla nitens

- Gray Silky-flycatcher, Ptiliogonys cinereus

- Long-tailed Silky-flycatcher, Ptiliogonys caudatus

Hylocitreidae: Hylocitrea Fjeldså, Ericson, Johannson, & Zuccon, 2015

1 genus, 1 species HBW-10

Hylocitrea was thought to be a whistler, then (Jønsson et al., 2008) suggested it might be a sylvioid. Spellman et al. (2008) found it nested in the Bombycilloidae, near Hypocolius. Oliveros et al. (2019) consider the Hylocitreidae and Hypocoliidae to be separate branches in Bombycilloidae, while Zhao et al. (2025) consider them sister taxa.

- Hylocitrea, Hylocitrea bonensis

Hypocoliidae: Hypocolius Delacour & Amadon, 1949

1 genus, 1 species HBW-10

Hypocolius has been considered of uncertain affinities, but Spellman et al. placed it firmly in the Bombycilloidae. Both Oliveros et al. (2019) and Zhao et al. (2025) found it near Hylocitrea and in a clade with that and the Hawaiian honeyeaters.

- Gray Hypocolius, Hypocolius ampelinus

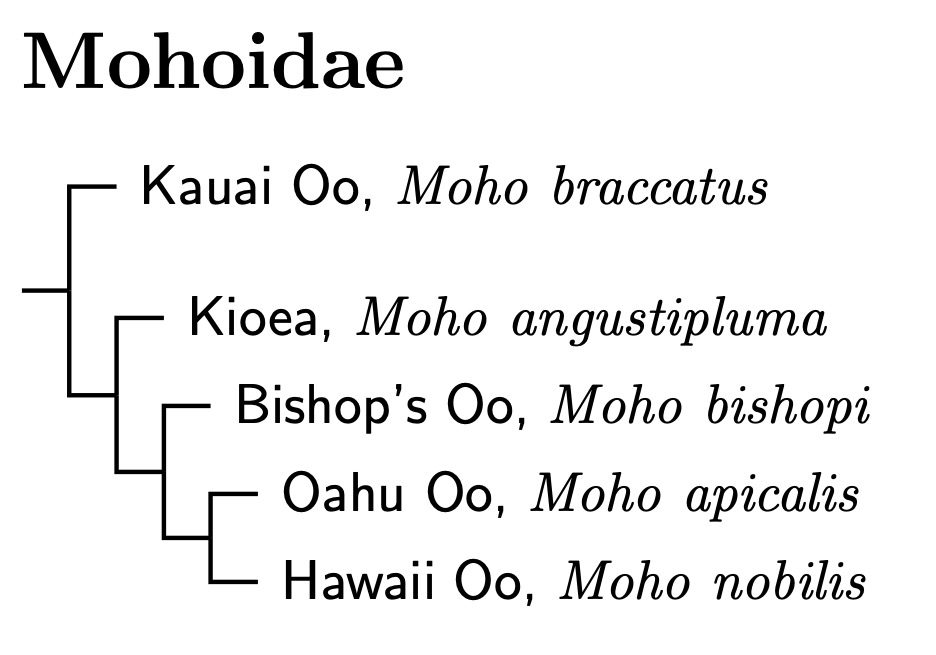

Mohoidae: Hawaiian Honeyeaters Fleischer et al., 2008

1 genus, 5 species Not HBW Family

The extinct Hawaiian honeyeaters were long thought to be part of the

basal oscine family Meliphagidae, which has spread widely across the

Pacific. Fleischer, James, and Olson (2008) have shown they are actually

related to waxwings. The Mohoidae are an impressive example of

convergent evolution. They look nothing like their relatives, but

instead appear very similar to honeyeaters with similar island

lifestyles. Zhao et al. (2025) sequenced all five of the Mohoidae.

The extinct Hawaiian honeyeaters were long thought to be part of the

basal oscine family Meliphagidae, which has spread widely across the

Pacific. Fleischer, James, and Olson (2008) have shown they are actually

related to waxwings. The Mohoidae are an impressive example of

convergent evolution. They look nothing like their relatives, but

instead appear very similar to honeyeaters with similar island

lifestyles. Zhao et al. (2025) sequenced all five of the Mohoidae.

- †Kauai Oo, Moho braccatus

- †Kioea, Moho angustipluma

- †Bishop's Oo, Moho bishopi

- †Oahu Oo, Moho apicalis

- †Hawaii Oo, Moho nobilis

Reguloidae

The kinglets may be the first to split off within Muscicapoidea, or maybe they group with the Bombycilloidae and both with Certhioidae. Either option finds support from Barker et al. (2004), Treplin et al. (2008) or Johansson et al. (2008b). Either option leads to the same linear order. I'm now treating the situation as a polytomy, in the order Reguloidae, Bombycilloidae, Muscicapoidae. The continued uncertainty about how the pieces fit together is a major reason for retaining separate superfamilies (see also Spicer and Dunipace, 2004; Voelker and Spellman, 2004; Zuccon et al., 2006; Reddy and Cracraft, 2007). It's also possible that that the Hyliotidae also belong somewhere around here, although that is starting to look less likely.

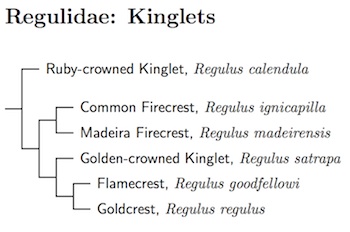

Regulidae: Kinglets Vigors, 1825

2 genera, 6 species HBW-11

The taxonomy of the kinglets is based on Päckert et al. (2009, 2012b). Most of the kinglets and crests are fairly closely related. We will leave them all in the genus Regulus. However, the split between Corthylio and Regulus is quite deep. Both Päckert et al. (2012b) and Oliveros et al. (2019) date it around 12 million years ago. Accordingly, I've placed the Ruby-crowned Kinglet in the monotypic genus Corthylio Cabanis 1853. That makes it Corthylio calendula.

- Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Corthylio calendula

- Common Firecrest, Regulus ignicapilla

- Madeira Firecrest, Regulus madeirensis

- Golden-crowned Kinglet, Regulus satrapa

- Flamecrest, Regulus goodfellowi

- Goldcrest, Regulus regulus